Fiberglass has become a ubiquitous product in today’s world. You almost certainly have several fiberglass products in your home (or even on it). In 2020, total global glass fiber demand totaled 10.7 billion pounds. And yet, just 100 years ago, total demand was about zero.

So how did we get here? This post tells the fascinating story of the creation of fiberglass and how it became one of the most important industrial products.

Before diving in, we should clarify our terms. “Fiberglass” is actually used to refer to two distinct things. Sometimes, the term refers to glass fibers, which can be found, for instance, in insulation.

On the other hand, the term is also used to refer to a combination of glass fibers and a polymer matrix, such as the fiberglass hull of a speedboat. A more accurate term for the latter is “FRP,” or “Fiber Reinforced Polymer.” We’ll use that term in what follows to avoid confusion.

Early Experiments with Glass Fibers

If you’ve ever had the chance to see a glassblower at work, perhaps you’ve seen molten glass being drawn out into surprisingly fine strands. There’s nothing particularly challenging about that. We know that the ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, and Greeks understood how to make delicate glass threads and used them for decorative purposes.

But making some strands by hand and producing a large number of very fine glass fibers are two different things. In the 1800s, people in various places began experimenting with techniques to achieve this much harder result. The first patent in the US for the production of glass fiber was issued to Hermann Hammesfahr in 1880. He developed a cloth woven from glass fibers and silk.

His patent was purchased by Libbey Glass of Toledo, OH, which produced lampshades and a dress made from the cloth for display at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. The dress received a lot of attention, though commercial applications would have to wait for further developments.

A Key Breakthrough

Those developments came in 1932. The depression was felt acutely by glassmaker Owens-Illinois in Toledo, OH, as the economic downturn lowered demand for glass bottles. Games Slayter, an engineer at the company, was working on ways to produce glass fibers as a strategy for finding new markets for glass.

Another employee at Owens-Illinois, Dale Kleist, was experimenting with fusing glass blocks together using molten glass sprayed from a gun originally designed to spray molten bronze. When he attempted to spray the glass, however, the gun emitted instead a shower of fine glass strands. Slayter immediately saw the potential of this accidental discovery and honed a process to produce large quantities of glass fiber efficiently and cheaply, which was patented in 1933.

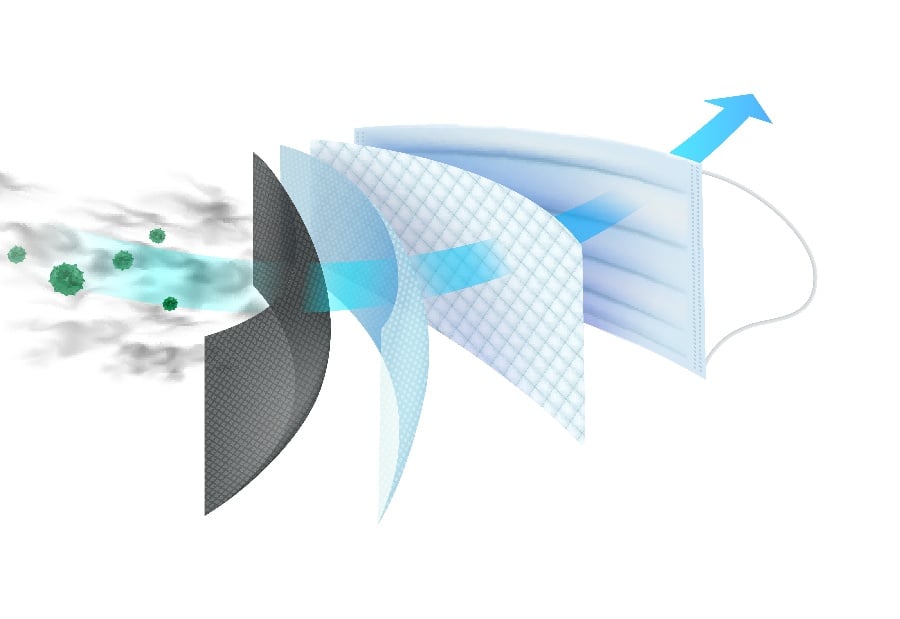

The first product Slayter made with these new glass fibers was an air filter, which went on the market in 1932. This was to be the first commercially successful glass-fiber product.

At the same time, Corning Glass of New York was also developing methods for producing glass fibers. The company approached Owens-Illinois to collaborate on research. In 1938, these companies formed the Owens-Corning Fiberglas Company (their name for the product had only one ‘s’), which continued to perfect techniques of industrial glass fiber production.

The Creation of FRP

Very soon after the discovery of methods to produce glass fiber in commercial quantities, engineers realized its potential as a reinforcing material in composites. The idea itself wasn’t new. Chemist Leo Baekeland, who invented the first synthetic plastic, Bakelite, in 1907, used asbestos fibers to reinforce it.

During WWII, glass fibers were embedded in various resins to create the first examples of FRP. The early examples were used exclusively in military applications, particularly for aircraft parts.

An important breakthrough came in the development of a polyester resin called Laminac, produced by American Cyanamid in 1943. Whereas previous polymers had to be cured with high heat, this polymer could be used and cured (using a hardener additive) at room temperature. This allowed for much greater flexibility in FRP fabrication.

Soon after this resin became available, the first FRP boat was built in Toledo by Ray Greene. In 1945, an FRP car prototype, called the Scarab, was built and driven across the country. In the 1950s, FRP using glass fibers gradually expanded into the range of products we associate with it today.

Fiberglass Today

The manufacturing process for fiberglass has changed somewhat since the innovations of Kleist and Slayter. Their method of subjecting a stream of molten glass to pressurized air or steam is still in use, though in an updated form. The more common method of production involves forcing molten glass through tiny nozzles to create fine strands, which are then drawn into a spool.

Different types of glass fibers are produced depending on the application of the finished product. The kind of glass fibers used in insulation, for example, are created in such a way as to trap lots of pockets of air in the glass. This has obvious advantages for a product used to insulate. Some classes are designed to have higher tensile strength, while others are formulated to be especially resistant to certain chemicals or environmental conditions.

The most common applications of fiberglass are in the building industry. Most new houses use fiberglass insulation, and standard asphalt shingles also contain fiberglass reinforcement.

In addition, fiberglass reinforced with resins is used in numerous applications where a strong, lightweight, and highly durable material is required. This includes components used in the automotive and aviation industries, boat construction, sporting equipment, storage tanks, shower stalls, and many other applications.

FRP use in construction and industry continues to expand because of the useful properties of this versatile composite. At Tencom, we have seen this growth firsthand as we have continually developed our expertise and capacity to produce pultruded fiberglass products while evolving our manufacturing processes. If you’d like to learn more about what fiberglass can do for you, please get in touch.

Post Summary

The article traces the evolution of fiberglass from an ancient decorative material to a vital modern industrial product, with global glass fiber demand reaching 10.7 billion pounds in 2020.

Key distinctions are clarified: "fiberglass" may refer to glass fibers alone (e.g., in insulation) or fiber-reinforced polymers (FRP), the composite of glass fibers embedded in a polymer matrix (e.g., boat hulls).

Historical Origins

Ancient civilizations, such as the Egyptians, Phoenicians, and Greeks, manually drew glass threads for decoration. In the 19th century, experiments advanced, leading to the first U.S. patent in 1880 by Hermann Hammesfahr for glass fiber cloth, showcased in novelty items at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Industrial Breakthroughs in the 1930s

During the Great Depression, engineers at Owens-Illinois, including Games Slayter and Dale Kleist, accidentally discovered a method to produce fine glass fibers using compressed air on molten glass in 1932. This was refined and patented in 1933, enabling mass production. The first commercial application was an air filter.

In 1938, Owens-Illinois partnered with Corning Glass Works to form Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corporation, advancing large-scale manufacturing.

Development of FRP

Post-discovery, glass fibers were used to reinforce polymers. World War II spurred military applications, particularly in aircraft. A pivotal advancement was the 1943 Laminac polyester resin by American Cyanamid, which cured at room temperature, facilitating easier production. Early civilian uses included the first FRP boat (circa 1942–1945) and an FRP car prototype (Scarab, 1945), with broader adoption in the 1950s.

Contemporary Status

Modern production primarily extrudes molten glass through nozzles, with fibers customized for properties like insulation (air-trapping), tensile strength, or chemical resistance.

Fiberglass applications dominate construction (e.g., home insulation, asphalt shingles) and extend to automotive, aerospace, marine, sporting goods, and industrial uses due to its strength, lightness, and durability. The article notes ongoing growth in FRP, highlighting its versatility.